- Home>

- News & Stories>

- “Dark” to Dawn: A Lesson in Living

“Dark” to Dawn: A Lesson in Living

“Dark” to Dawn: A Lesson in Living

By Justino Aguila, San Francisco ExaminerDeath. Organ donors. Liver transplants. These terms were part of a recent lesson for dozens of students at Ida B. Wells High School in San Francisco.

It was a lesson in saving lives as told by siblings Jeffrey and Wendy Marx. Their story takes place in a San Francisco hospital more than a decade ago.

Back then, 22-year-old Wendy Marx had just graduated from college, packed her belongings and made the cross-country trip from Connecticut to The City, a place she had long wanted to explore.

But soon after her arrival, she began feeling extremely tired and lost her appetite. She knew something wasn’t right. A doctor diagnosed her with hepatitis B. Later, he would tell her family that without a liver transplant, she would die within 24 hours.

“I was never sick a day in my life,” Wendy Marx said. “I thought I was never going to be normal.”

A month after being diagnosed, Marx was hospitalized and drifted into a coma. The chances of receiving a liver transplant seemed slim. But prayers were answered. A donor came through.

Even with the liver, which came from a 9-year-old boy who died in an accident, Wendy had a 50-50 survival rate.

“Standing over her bed while she was in a coma was by far the most difficult, life-changing experience that I had ever had,” said Jeffrey Marx, now 37. “She only had hours to live.”

It was during his sister’s wait for a transplant that Jeffrey Marx, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, vowed to begin a personal crusade to spread the word about the lack of organ donors in the United States.

The most sense I can make out of this is to help create a different world.

Each day, more than a dozen people in the United States die waiting for an organ transplant. At the start of this year, more than 66,000 people were on the national waiting list for a transplant of some kind.

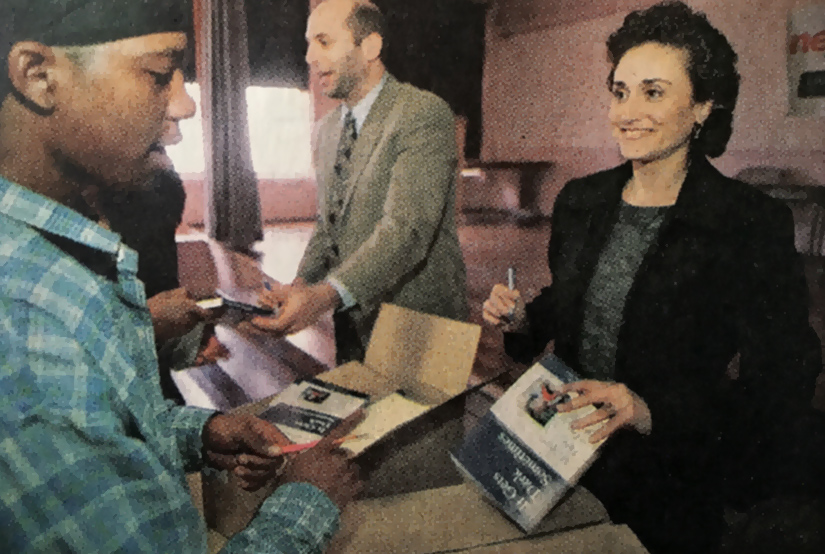

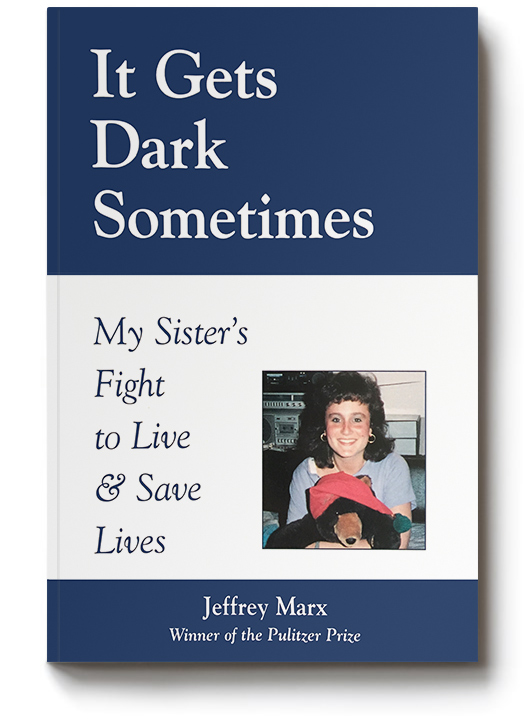

The results of those experiences are now detailed in his self-published book, “It Gets Dark Sometimes: My Sister’s Fight to Live and Save Lives.” He began the West Coast leg of a national book tour in San Francisco last week.

The book chronicles his sister’s life from the fight to stay alive to her second liver transplant in 1992.

“I'm glad they’re educating people,” said Chantelle Faison, 16, a student at Ida B. Wells High who along with her classmates received free copies of Jeffrey Marx’s book. “People don’t like to talk about these things, but it’s something that everyone should think about.”

Unlike some of her classmates who squirmed at the idea of donating an organ, Faison knew the importance of donors. Her 8-year-old sister Jerrace Brown died in 1998 after suffering an asthma attack. Her organs were donated and helped save lives, Faison said.

The lack of organ donors is unacceptable for the Marx siblings.

“The most sense I can make out of this is to help create a different world,” said Wendy Marx, who is managing producer of health programs for Thrive, a subsidiary of Oxygen Media Inc. “Whether that means to increase donor awareness or participate in clinical trials, that’s my purpose in life.”

At the time of Wendy Marx’s first transplant in 1989, there were 700 people on the waiting list for a liver. Today, there are more than 14,000.

Wendy Marx was catapulted to the top of a national waiting list in 1989 because she was very close to dying, which can be a primary factor for someone getting to the top of a list.

Hepatitis B destroys the liver with advancing scar tissue, which may shut down the liver, said Robert Gish, Wendy Marx’s doctor. Gish is the medical director of the liver transplant program at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco.

A small number of people like Wendy Marx get severe acute hepatitis B, which means they have more complications and in some cases need a new liver.

Although Wendy Marx suspects an oral surgeon was the source of her disease, her doctor said they really “have no idea how she got it.”

About two years after her 1989 liver transplant, hepatitis B flared up and destroyed the new liver. Wendy Marx then had a second transplant.

She takes 13 pills a day and said she is living the normal life she dreamed of after being diagnosed with her illness more than 10 years ago.

Gish said her liver will be in good shape for two to five years, but eventually will have to be replaced. Marx is already on another waiting list for a liver, he said.

“I acknowledge that I will need a new liver,” Wendy Marx said. “But I have also moved beyond that. I live every day to the fullest and expect to live a long and healthy future.”